The Trust launched a new initiative, calling for submissions from members of the public, researchers and thinkers to send in 'burning' historical questions which could feature and be answered in our Notes & Queries section of a future edition of the Gibraltar Heritage Journal. We asked for thought-provoking questions which had not been discussed, explored or answered in the wider literature of Gibraltar's history.

We would like to thank everyone who submitted a question and are pleased to share some of our findings and answers to your questions below. Others may feature in upcoming Journals.

Q&As:

A: Gibraltar is popularly supposed to be named after Tarik ibn Zeyad, the Berber Muslim general who is supposed to have landed in or near Gibraltar on the way to conquer Visigothic Spain. The Arabic “Gebel-Tarik” or “Gebel-al-tarik” (Mountain of Tarik) was contracted over the years to the present “Gibraltar.”

Other origins have been suggested.1

A: Nothing to do with the English word ‘altar.’ It’s simply the retained syllables of ‘al-tarik.’

A: The Greeks gave the peninsula the name “Iberia,” probably from the river Ebro (they had a trading post nearby called Empurios – hence the word “Emporium”. Later the Romans called it “Hispania”, probably from the Phoenician name which means “Land of Rabbits.” The original Greek name is preferred, as it does not imply that the whole peninsula belongs to one nation.

Fun fact: The Hebrew name for the peninsula is Ha-Sepharad, and the Hebrew consonants in the name ( H – S - Ph – R - D ) are very similar to the Greek HeSPeRiDes – the islands where Heracles found the golden apples – Seville Oranges, maybe!

A: It isn’t.

A: “Campo” is not “camp” in Spanish, but refers to fields or an area of land. The “Campo de Gibraltar” was the area administered by the City of Gibraltar in Spanish times. The name of the village of Campamento does refer to the encampment of Spanish/French troops during the Great Siege.

1 Sassoon, H. “Two views of the Arab invasion and Tariq/Tarif.” Gibraltar Heritage Journal, Vol 10, p. 5;

Benady, S. What’s in a name? Origin of the name ‘Gibraltar’ revisited. Gibraltar Heritage Journal, Vol. 22. p. 7.

(all answers by Sam Benady)

*********************************************************************************************

A: The period 1705-1712 is a confusing period in Gibraltar's history, but this publication has already published two of my studies: "The Early Governors I," in issue 9, and "The Depositions of the Spanish Inhabitants to the Inspectors of the Army in 1712," in issue 6.

The latter also appeared in Almoraima 13, and I will present some clarifications of the former at the upcoming Jornadas de Historia next April. My work is based on papers from the British National Archive, the British Library, and the Archivio di Statto di Genova. According to the book, "The First Peninsular War," by A.D. Francis, there is nothing of interest in the Vienna archives, but I may be mistaken.

If you find anything else of interest, the Journal is willing to study it. I'd like to take this opportunity to congratulate you on your book and thank you for your efforts to strengthen the ties between Menorca and Gibraltar.

(By Tito Benady)

********************************************************************************************

A: Refer to article 'The Settlement of the Jews in Gibraltar, 1704-1738' in Gibraltar Heritage Journal Special Edition (2004).

*********************************************************************************************

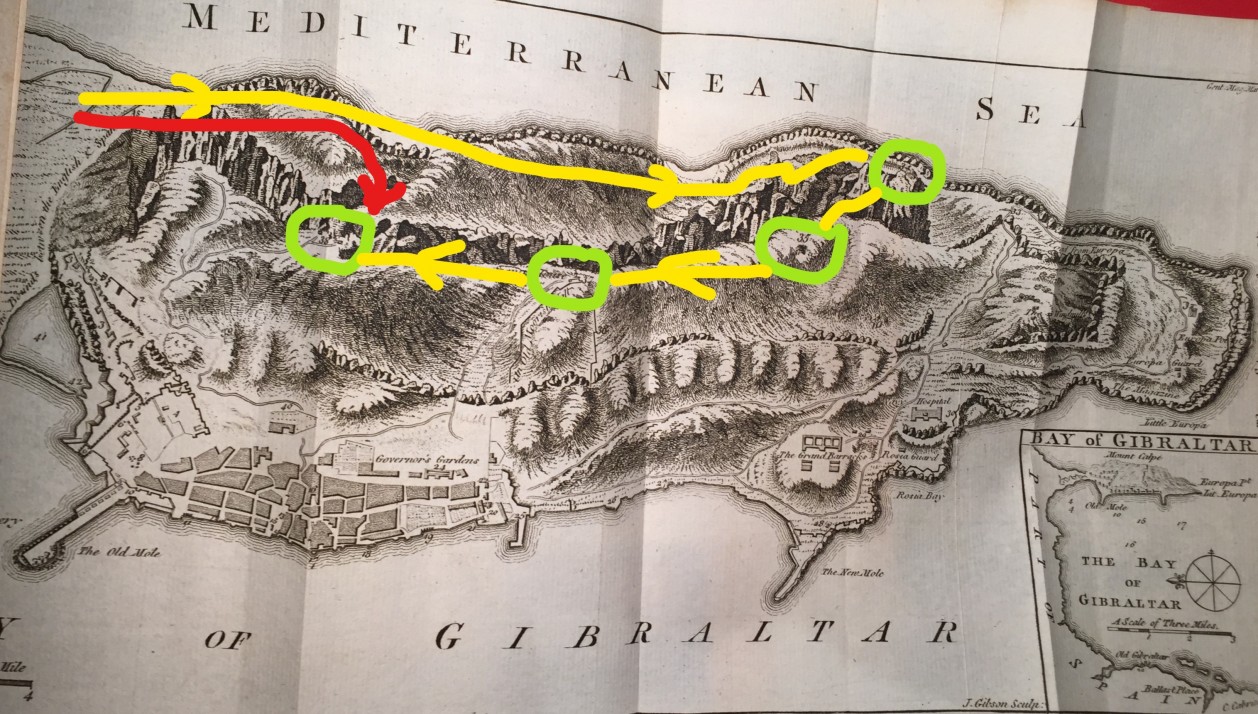

A: The goatherd’s path was the subject of an article I wrote in the Heritage Trust Journal No 18 (2011). The story in a nutshell is that there was a weak spot at Middle Hill behind Catalan Bay that could be taken from the slopes on the Eastside if it was not defended. Susarte knowing the paths around the Rock led what was effective a small raiding party of 500 Spanish soldiers to capture Middle Hill using a route that went along Sandy Bay and along the cliffs to where Monkey’s Cave is today. This location was called the ‘pass of the locust trees’ or ‘el paso del algarrobo’ which is identified (34) on a map in the Gentleman’s Magazine of March 1762. This pass was subsequently scarped by the British and a guard house built near Monkey’s Cave, both confirmed by James and Drinkwater. The attack by Susarte was initially successful but unfortunately for his companions, the French did not follow through with the agreed assault from Catalan Bay and the raiders were abandoned to their fate. Given the extensive quarrying of the slopes behind Catalan Bay and Sandy Bay in the building of the dockyard it would not be possible to recreate either path.

Key to Map:

Yellow – Spanish

34 – ‘el paso del algarrobo’

35 – St Michael’s Cave (Stayed the night)

37 – Signal Station – Killed the guard

38 – Middle Hill guard captured

Red – French - Intended route up slope behind Catalan Bay

(By Roy Clinton)

***********************************************************************************************

A: The two liners were in Gibraltar by an arrangement through the Red Cross that a large number of Italian women and children in Somalia who were in Prisoner of War Camps should be repatriated. In Gibraltar each ship picked up an armed military group to ensure they stuck to the agreed course. They were not allowed through the Suez Canal in case of sabotage and had a long journey round Africa, therefore tankers were also sent to refuel them.

(By Tito Benady)

************************************************************************************************

A.

Slaves in Gibraltar

When Gibraltar was ruled by the Muslims there were no doubt slaves in Gibraltar. These would have been largely European Christians, especially from the Iberian peninsula. When Gibraltar was captured by Castile in 1462, there were no doubt slaves, but these would have been Muslims from Granada or North Africa, and maybe some Jews.

The Archives of the Diocese of Cadiz 1 have numerous mentions of slaves: for example, in page 100 we have the marriage of Juan Caballero and Ana González born in Angola. Both were slaves, and their ‘owners’ were citizens of Gibraltar.

After 1704, there is some evidence of slaves living in Gibraltar, but they probably were not many. 2 The 1777 census in the Gibraltar Government Archives records (in the list of Jewish inhabitants) one Bumper “a negroe” aged 40, from Guinea, but he is not recorded as a slave and was probably a paid servant.

The Slave Trade

Gibraltar was never directly involved in the slave trade, but slaver ships on the way to Africa would call in at Gibraltar to stock up with trade goods such as linens, as British goods were prized above others by the Africans who sold their captives to the slave traders.

When Britain abolished the slave trade, this practice had to stop, and in 1829 Lieutenant Governor Sir George Don decreed that any ship suspected of being a slaver was banned from provisioning in Gibraltar, and the British Consuls in Cadiz and other Spanish ports (where the ships were outfitted with the necessary shackles and chains) were ordered to report any suspicious ships which might be heading for Gibraltar, and such ships were rigorously examined when they arrived. 3

Fun Fact: Mrs Elizabeth Robinson, a long-time resident in Gibraltar, travelled to London and was the first woman ever to give evidence in the House of Lords – on slave trafficking! There is no indication, though, that her evidence concerned Gibraltar. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_the_House_of_Lords)

1 Anton Solé, P. Catálogo de la sección “Gibraltar” del archivo histórico diocesano de Cadiz 1518-1806. Cadiz, 1979.

2 Garcia, RJM. Ordinary Life in Peace and War. RJMG Books, Gibraltar,2021, p. 145.

3 Benady, S. General Sir George Don. Gibraltar Books, 2006, pp. 105-106.

(By Sam Benady)

**************************************************************************************************